Assisted Living

By James W. Morris

Living Together

In order to save themselves money, Mr. Hirsh and Mr. O’Donnell, though previously only nodding acquaintances, decided to share an apartment at the large retirement community in which they resided. Both were recent widowers with long, happy marriages to their credit, so theoretically each knew how to live in close quarters with another person without prompting overmuch annoyance from the other party.

Repressed Complaints

If they had been complainers, after only a few weeks Mr. Hirsh would have felt justified saying something about the excessive frequency of visits to their small apartment from Mr. O’Donnell’s divorced and obviously lonely daughter, and Mr. O’Donnell might well have remarked about the thundering decibel level at which Mr. Hirsh played the television set while watching his old western movies ― but they didn’t complain, not to each other, anyway.

Mr. Hirsh’s Stories

Mr. Hirsh told Mr. O’Donnell that as a young man just out of high school he had written comedy for some rather famous radio personalities, before the advent of television made a transition into an advertising career seem a wise choice. Jack Benny, Fred Allen, George and Gracie, Fibber McGee and Molly: Mr. Hirsh claimed to have known and written for all of those performers, and he had a full storehouse of genuinely funny, often retold anecdotes (many of them at least somewhat ribald) to prove it. Mr. O’Donnell was a full decade younger than Mr. Hirsh, and not so familiar with the vaunted heyday of radio, but he generally enjoyed hearing the older man’s well-practiced recitations about those days, though you’d never

know it by looking at his face while they were being related ― a retired high school principal, Mr. O’Donnell wore the seemingly permanent expression of someone about to correct a stack of term papers.

After their first two months together, Mr. O’Donnell knew Mr. Hirsh’s stories well enough to take note that quips and gossip previously attributed by Mr. Hirsh to one radio personality (Jack Benny, say) were in later retellings often as not attributed to someone else (George Burns, for example). Mr. O’Donnell was the sort of man who cherished consistency as a prime virtue in other people, but for some reason he didn’t find Mr. Hirsh’s inconstancy regarding the details of his stories at all annoying; his new roommate was simply too funny and likeable to be irritated by.

Mr. Hirsh Goes Quiet

After the two men had lived together for three months, a day came when Mr. Hirsh abruptly stopped telling his stories. In fact, he practically stopped speaking to Mr. O’Donnell altogether, except for polite exchanges when absolutely necessary. Had Mr. O’Donnell done or said something ― something indicating annoyance or boredom with his new friend’s conversation ― that caused Mr. Hirsh’s sudden reticence? Mr. O’Donnell didn’t think so.

Mr. O’Donnell wondered: was Mr. Hirsh sick? Was he angry, bored, depressed, suicidal, or, God forbid, homicidal? Or did the other man just, for whatever reason, suddenly feel like keeping silent? Despite their status as roommates, Mr. O’Donnell didn’t feel he knew Mr. Hirsh well enough to question him closely about it.

Mr. Hirsh Stops Sleeping

On several successive nights, Mr. O’Donnell, having crept out of bed in order to visit their tiny shared bathroom (due to the promptings of a cranky enlarged prostate), on his way spied, through a door left ajar, Mr. Hirsh awake, sitting in a chair in the living room, in the dark, murmuring to himself. What was he doing? Praying? Mr. Hirsh was not a religious man as far as Mr. O’Donnell knew, though they could hardly have been said to have discussed that aspect of his life to any significant degree ― people just getting to know each other are better off avoiding delicate topics like religion.

Perhaps it was simple old age insomnia, Mr. O’Donnell thought. But after five consecutive nights of seeing the other man wakeful he decided to say something.

“Bernie,” Mr. O’Donnell said as they faced each other over the breakfast table the next morning, “I notice you’re not sleeping very well lately. Anything on your mind?”

Mr. Hirsh rolled his eyes Mr. O’Donnell’s way. The eyes were bleary, rimmed with red. “You really want to know?” he said at last.

Mr. O’Donnell felt a prescient chill go through him upon hearing those words, though why such an extreme reaction was fostered by Mr. Hirsh’s simple question he wouldn’t have been able to say. What he did say was: “Sure Bernie, if you think I might help.”

Mr. Hirsh snorted and contorted his face into something only slightly resembling a smile. “Frankly, I doubt it, Red. I think it’s more likely you’ll turn me in to the mental health people.”

Mr. O’Donnell stopped chewing. “It can’t be that bad,” he said.

Mr. Hirsh just shook his head.

“Look, Bernie. I’m an old man, too. We all have trouble sleeping sometimes. There’s that special kind of deep, hopeless boredom that seems to be set aside only for the elderly ― I’ve felt that. Or maybe you’re afraid of dying; it’s more of a reality the closer it gets, right? Comes with the territory. Or you’re looking over your long life, adding up the joys and regrets. I’ve done that, and before you know it, it’s morning and you’ve let a whole night slip past. So just tell me you’re okay and I’ll mind my own business.”

Mr. Hirsh looked at Mr. O’Donnell for a long time. Then he said, “You know, you’re all right, Red. I wish it was the kind of ordinary stuff you mentioned. But it’s not.”

And then he went silent again.

Corned Beef and Cabbage

The price of one meal per day was included in the rent of their assisted living facility, so as a rule Mr. Hirsh and Mr. O’Donnell ate their breakfasts and lunches in their apartment, and then at dinnertime strolled over together through the building’s winding corridors to the expansive cafeteria; they believed that the dinners served there were more palatable than the meals offered earlier in the day. But then the day came when Mr. Hirsh told Mr. O’Donnell to go to dinner by himself.

“You want me to bring you something?” Mr. O’Donnell asked him.

Mr. Hirsh shook his head no.

When Mr. O’Donnell returned to their apartment more than an hour later, he found Mr. Hirsh sitting in the same chair in which he’d left him, staring straight ahead, seemingly frozen with inertia; it was as if all of the impetus for living had drained out of the man.

Mr. O’Donnell adopted a cheery tone. “Well, you missed it, Bernie. They served corned beef and cabbage for dinner tonight. My grandmother used to make it, my mother too. Of course, they – Gram and Mam ― weren’t able to infuse it with that unique institutional tang that they do here. But it was really rather brave of the kitchen staff, don’t you think? To serve cabbage to a huge group of old people ― in a confined space? The atmosphere will never be the same.”

Mr. Hirsh had nothing to say.

Mr. O’Donnell Loses Patience

“Damn it, Bernie,” he said, looking hard into the other man’s face. “If you don’t start talking to me I’m going to do something desperate.” Here he paused, trying to think of something desperate. “That’s it!” he said. “I’m going to invite Bernice Blodgett over for cocktails every night.”

Bernice Blodgett was a foggy-headed eighty-seven year old widow who had an unexplained but severe sexual crush on Mr. Hirsh, propositioning him at every opportunity, and trailing behind him with her walker ― her tiny feet scuffling along the carpet ― wherever he went. Mr. Hirsh was too kind to report his elderly would-be seductress to her family, or anyone else who might be in authority over her, fearing that they would confine her in some way, and knowing all too well how precious physical freedom can be to a person of her age, since he was only three years younger.

Nonetheless, he was desperate to avoid the woman’s grasping clutches, to which he felt especially vulnerable since he was a slow walker himself, his twin knee replacements requiring him always to use a cane. However, at maximum hobble Mr. Hirsh was just slightly faster than Bernice, and virtually everyone living in the facility liked to witness the couple’s low-speed chase scenes in the hallways, punctuating the tableau with comments like, “Go, baby, go!” as, one hotly in pursuit of the other, the elderly pair raced by with excruciating slowness.

Bernie smiled, the first genuine smile Mr. O’Donnell had seen on his face in at least a week. He put his hands up, as if in surrender.

“No, no, Red. Anything but that. That old bat drives me nuts. Did I ever tell you the filthy things she whispers to me when she gets a chance? And her a great-grandmother.”

Mr. O’Donnell went to a cabinet and pulled out a bottle of wine from a case his daughter had given him; he knew Mr. Hirsh liked a glass of wine now and again. “Why don’t we have a glass of this, Bernie? It’ll loosen your tongue, and I’ll promise not to turn you in to the rubber-room people, no matter what you say.”

Mr. Hirsh Talks at Last

“Well, it started, what? Only a week ago, maybe less, I’ve lost track of time. My head is all fuzzy, whether it’s from too little sleep or too much fear, I don’t know anymore. I’m sorry to burden you with all this, Red. Anyway, where was I? A week ago, a regular night. You went to bed early, I think. I stayed up for a while, there was a good western on. Shane. Anyway, when it was over I hauled myself off to bed.

“As I was lying there, waiting for sleep, I experienced a very peculiar, but definite physical sensation. It seemed that someone, standing silently by my bed in the dark, had encircled the big toe on my right foot with their fingers; I could feel the hand tightening around it. Of course, I yelped, yanked my foot away, sat up, turned on the light. No one there. The apartment was quiet. It occurred to me that the person grabbing my toe was you, playing a practical joke or something. But then I realized that that was ridiculous, why would you do that? And how could you disappear so completely when I turned on the light? I could hear you snoring in the other room. But if it wasn’t you, who was it?

“It felt so real, so absolutely real. After a minute I calmed down a little and had to concede that I’d dreamed the feeling, though there was nothing dreamlike about it, and I was sure I hadn’t quite fallen asleep yet when I had it. But what other explanation was there? Once the pounding of my heart quieted a bit, I turned out the light and tried to go to sleep again. As soon as I did, as soon as sleep started to overtake me, I felt the fingers – strong as steel – circling my toe again, and this time pulling on it. Of course, I sat up, turned on the light, pulled my foot away. No one there. I got no sleep at all that night, needless to say. I just went to the living room and watched the TV. Well, I figured, I’m eight-four years old and retired. What did it matter if I missed a night’s sleep? It was not like I had to go to work the next day, I

thought.

“The following night I was so tired I predicted I’d go right to sleep without having a chance to think about toes, and what imaginary beings might be likely to pull on them. But as soon as I shut out the light, there it was, the hand grabbing my toe and pulling on it, trying to take me somewhere. Yes, I knew that, suddenly. That the hand was attempting to take me away to another place, somewhere my instinct very fiercely told me I did not want to go. I should say I’m not a believer in all that heaven and hell jazz, Red, no offence if you are. But I didn’t think the hand was planning on escorting me to the plain old afterlife anyway, if there is one. It felt too… menacing for that.

“You know, I never really told anyone this, but when I was a kid we used to visit my grandparents, my mother’s parents, quite a lot, and my grandfather – he must have been ninety by then, a really old man by the standards of the day ― anyway, he took me aside one afternoon and told me that he would be dying soon, and that lately, when he was sitting alone in his study ― he was a retired judge ― that he often felt a hand on him, a gentle welcoming tap on his shoulder, an invitation. He said that one day soon he would accept that invitation, and he was right. But those touches, the way he described them, were friendly.

“Mine aren’t. So what have I been doing? In the past week, I’ve tried sleeping with the light on. I’ve tried sleeping in the living room. I’ve prayed. I’ve worn a boot. I even briefly considered cutting my toe off. Crazy, right? Anything I could think of. I can doze a little, but always, as soon as I approach real sleep, I feel the fingers around my toe. I know what will happen, Red.

“Some night soon I’ll fall deep asleep despite feeling the hand on me. I’ll have to, a person can’t go without sleep forever, am I right? And then the hand will take me, take me back to whatever horrible place it comes from.”

Mr. O’Donnell Has an Idea

Red O’Donnell was silent for a long time. He certainly hadn’t expected to hear anything like what he’d heard from Mr. Hirsh’s mouth, though he didn’t doubt the man’s sincerity for one moment. All a person had to do was look in Mr. Hirsh’s face to see that he was petrified by what was happening to him.

They had finished a second bottle by the time Red spoke.

“Well, Bernie, my friend, that’s quite a story,” he said. “And I want you to know that I believe you, that I believe that you’re telling the truth as far as you know it, I mean. But from my perspective what is happening is this: on that first night you had a half-dreamed feeling, a frightening one, about some invisible someone yanking on your toe. Your mind was so scared by this experience that it now anticipates it, makes you feel it again whenever you turn out the light. And I know that that feeling is just as real as if someone actually was pulling on your toe ― that’s how powerful the human mind is. And you’ve gotten yourself trapped in this strange loop with seemingly no way out. However, I have an idea. It’s probably the kind of

idea someone gets only after drinking two bottles of wine, but here it is anyway.

“You’re never going to get rid of this feeling until you get a good night’s sleep and wake up with you toe still on, so why don’t you go to bed now? I’ll sit at the foot of your bed, and ― I can’t believe I’m saying this ― I’ll hang on to your big toe while you sleep. When you feel my hand, you’ll know that it’s only me, that it’s safe to go to sleep. In the morning you’ll feel a million times better.”

Bernie’s eyes widened. “But that’s crazy. One grown man sleeping while his roommate holds his toe?”

“Crazier than what’s happening to you?”

Bernie pondered. “Well, I have to try something, Red. That’s true. And if you’re willing to do it, I won’t try to talk you out of it. God knows I have to do something or go crazy.”

“Good. The last thing I need at this time in my life is a crazy roommate.”

The Next Morning

The sun found Red O’Donnell deeply asleep in a chair abutting the foot of Bernard Hirsh’s bed. All was quiet, except for the distant sounds of the retirement community’s slow awakening: coughs, murmured voices, a distant phone ringing twice before being picked up.

Red stirred a bit, grunted, took a deep breath, said his wife’s name, and then returned to sleep. His sleeping position was awkward, with his torso contorted, his head cocked crazily to one side, and his left arm still extended between the bars of Bernie’s footboard.

Finally, Red woke with a start and his first sensation upon waking was pain ― a throbbing hangover headache followed by a tremendously sharp spasm from his stiff and twisted neck. He felt paralyzed, leaden.

His eyelids were his most easily moved body part, so he willed them fully open. After a few seconds, the preposterous events of the previous night returned to him, to his unbelieving conscious mind, accompanied by a chastening surge of shame; he had meant to keep watch over his troubled friend, not fall asleep.

Then Red focused his bleary eyes on the bed before him, which was still cast in the deep, colorless shadows of early morning.

What he saw did not make sense.

The bed appeared unoccupied, empty, in fact, bereft. But ― wasn’t he still holding Bernie’s toe? Didn’t he have it safely in his hand? His muddled mind tried to work through the discrepancy between what he saw and what he felt.

Mr. O’Donnell’s Crime

As his mind cleared further that morning, the true nature of his, Red’s, own misjudgment was revealed to him, his unforgivable failure as a friend. He suddenly knew with certainty that Bernie Hirsh was not to be seen again, never coming back; his roommate was disappeared, lost to this ordinary world forever.

To prove the depth of his shame, Red overcame his paralysis and retracted his arm ― which ached fiercely from the awkward position in which it had spent the night ― brought his closed hand up into a weak beam of sunshine near his face, and then unfurled the cramped fingers.

Lying across his palm was the sad lump of flesh that had been Bernard Hirsh’s big toe, which, neatly severed, had grown cold.

James W. Morris is a graduate of LaSalle University, where he was awarded a scholarship for creative writing. He has published dozens of stories in various literary magazines, including Philadelphia Stories and Zahir. He has also written one play, “Rude Baby,” which was recently produced, and worked for a time as a joke writer for Jay Leno.

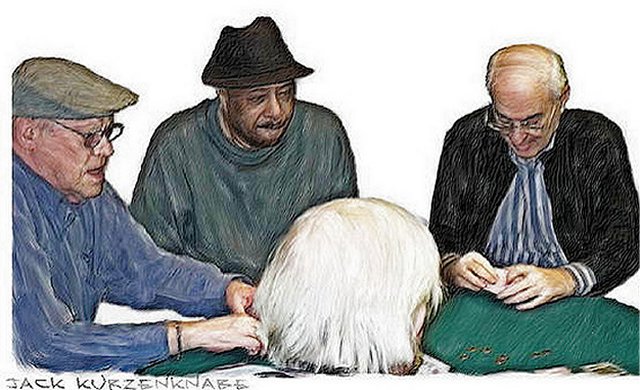

Featured image via Flickr, Jack Kurzenknabe, Public Domain